A chorus of car horns protests the morning traffic.

Mini buses bob and weave with video game madness, rushing to the center of the city to deposit their cargo of passengers.

Several of those passengers are children heading to school with unusual normality…unusual because they are the off-the-grid residents of Georgetown’s squatter settlements, many of them now third generation members, living with mothers and grandmothers…generation after generation, with quality of life molded by squatting.

Those who recall when the Airport was Atkinson Field might remember when it was a comparatively sterile building, sitting at the end of a sanitized roadway which began its scenic uphill climb right about where the Timehri Police station sat; following an idyllic stretch of roadway on which trees with symmetrically whitewashed trunks stood at attention – offering, at once, hearty welcome and fond farewell.

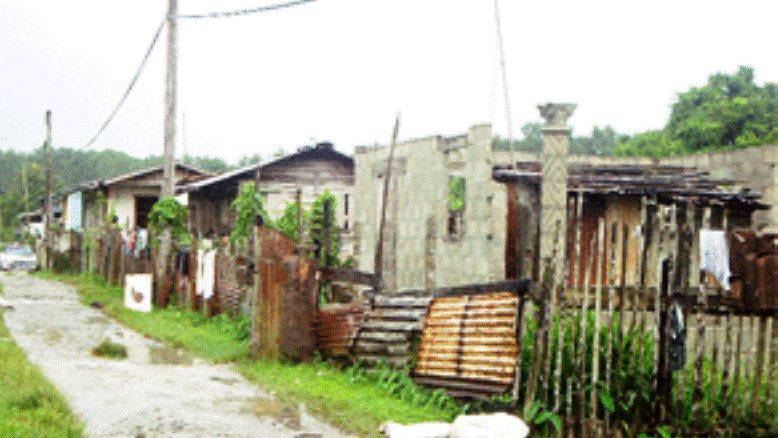

Decades later, the surroundings of the airport, the portal to the country’s capital, stand in stark contrast to modernity; to the political rhetoric of politicians past who dangled the carrot of infra structure, development and economic progress; promises we recall as we ride past the asymmetry of shacks and multi-storied mansions punctuated only by rubbish, scrawny chickens, donkey carts and an occasional cow too indifferent to care about the detriment of cars that go so fast they to idle at ninety miles per hour.

The imagery continues as the road winds and twists its way into the country’s capital, the city of Georgetown, once dubbed the Garden City, now tarnished by the fall out of bad politics and hopeless economics. Housing has been a historic challenge for this city which has been plagued with containing its population since after emancipation of its slaves and the release of its indentured laborers but the recent decades of government occupation by politicians – the People’s Progressive Party – with skewed agenda and invidious intent, has defaced the city with deep societal scars that now beg a steady political hand with a social scalpel.

Frustratingly, the ideologies of the two primary political parties have politicized the housing problem so much that it has obscured the fact that the city’ population expansion was an ever -evolving challenge. In the face of explaining the plight of squatters in a country that has 83,000 mostly uninhabited square miles and less than one million in population, politicians retreat to feel good stories.

The People’s Progressive Party likes to refer to Janet Jagan’s establishment of East and West Riumveldt in the late fifties and early sixties to alleviate the city’s squatting and the subsequent selling off of many of those homes for pennies on the dollar because the tenants had become technical squatters, having not paid rent to the Housing Authority for decades. Their point is that their party has a history of being sympathetic to the plight of squatting even when the squatting population is primarily of African descent.

On the other side, the People’s National Congress likes to site the housing projects established under Forbes Burnham and tout his programs for housing the nation. Their point is that their ideology was implemented to support the Constitution’s mandate to house the country’s citizens, irrespective of ethnicity.

Into the space, between political posturing and looping economic depression, flood more squatters, caught between the harsh reality of poverty and a politics that ignores them.

That space, which often lies beyond the manicured parapets, behind the concrete fences of middle and upper class domesticity, is another Georgetown where squalid is normality; where homes are a crude mash up of zinc and brick, a wedge of rotten wood, competing with the stench of floating sewage and poor drainage.

Yes, this is a country with a Constitution.

This Constitution has always upheld – in Chapter II 26- that every Guyanese has the right to proper housing accommodation. Proper, by context, dictates, implies, sanitation and safety, legislates housing in homes and on ground that is not inherently hazardous to occupants.

Yet, under successive governments, the relationship with squatters remains burdened with political indifference. We may recall that, right before the May 2015 general elections, the People’s Progressive Party’s declared a “regularization process” to combat the country’s squatting epidemic by extending loans to twenty one thousand squatters who had, they determined, built in “equity” into the land they had informally occupied.

There was much to question here.

Loans typically infer repayment. Repayment typically infers jobs. Many of these squatters are jobless and/or depend on income that is woefully inadequate. Indeed, the majority of people who squat are impoverished or underemployed.

But there are some who are not; who occupy with hopes of acquiring by default.

Politicians know this so this is why Irfan Ally’s regularization process based on “equity” built in to period of occupation came across with some political stench.

What would have been fair and proper would have been his announcement to introduce legislation to expropriate land ownership from the owners and pass title on to those who had been squatting; after his agency would have conducted a diligent investigation to confirm that the squatter was in fact destitute and was not just a part time squatter engaging in land grabbing.

What sits along the continuum of these cavalier proclamations, these politically motivated actions, is the obscuring of the relationship between cause and effect. Squatting in Guyana is the effect. The cause is far more intricate; woven into the socio political fabric of the country. There is direct connection between poverty and squatting. There is a direct correlation between quality of life and learning. There is a direct relationship between education and successful economies. Investing in human capital from primary education level and inclusive of any technical training is an investment in the country’s human capital and economic growth. Poverty impedes learning.

These are the threads of the fabric of society which, when unraveled, give us results we can ill afford – like our current rate of illiteracy, under performance in academic examinations, compromised academic curricula and matching levels of learning.

Offering palliatives is, typically, what politicians who have no intention of following through with promises do. So, the arbitrary proposal to extend loans was a tranquilizer, intended to sedate the squatter, to soothe him in to believing that the government was working for him. In an economy with un and under employment at peak levels, with job skills at the lower end of the graph, those who qualified for these loans based on their equity would have been lured into signing a document that would legally oust them from their property if they failed to pay. They would, essentially, be foreclosed against and will lose the equity and tenure that was ascribed to their period of squatting.

Talk about a Catch Twenty Two with a caveat… a squatter being lured into giving up squatting status for equity that is not really equity because the land is not his but the government is calling it equity to issue him a loan to make interest off it.. moe money…

It would be a comedy of errors if people’s lives and livelihood were not at stake.

These are people who have assets in stalls, shacks, gardens, livestock and poultry which they cannot pass on or use as collateral to get bank loans or expand their entrepreneurial endeavors.

Really, that analgesic solution offered by PPP – gamble your squatting status against a loan you may not be able to repay – effectively embalms their assets as dead capital.

The plan, which is not a novel approach, actually makes economic sense and is of national benefit when refined and implemented expressly for the advantage of the squatter and not the government. With land ownership, taxes can be collected which would increase city revenue. And, this is only one of the many rewards that giving title to the squatter offers.

But we are not sure what the details of the “regularization process” were under the government of the People’s Progressive Party. The Ministry of Housing and Water, through the Central Housing and Planning Authority never made clear the mechanics of this process except to say, conveniently around the election period of 2015, that it would benefit twenty one thousand squatters.

It would be interesting to learn if the “regularization process” that the PPP government sold as benefiting 85% of the squatting community actually serviced them. It would be interesting to know how many squatters have since lost their “property” to loan default and who now owns the land the previous squatter was evicted from….

The lorries belched and ground their way around Georgetown.

It was the day after the Coalition had won the general elections. In the air was a protracted feeling of revelry. People had voted for change and had gotten it. In addition to lorries were back hoes and people with spades and cutlasses and brooms and attitudes of pride in a city that was left to decay by a government that was more partisan than patriotic; a government that sought to punish a Mayor through denying funding to run a city. It mattered not that city was the country’s capital. It mattered that they were running things and had the reigns in their hands to belittle a party and yes, an ethnicity, with which this party has historically been at odds with.

The cleanup campaign was both a political victory and a populace catharsis. They cleaned up the trash, improved streetscapes and cleared away the eye sores that the ousted party had allowed to fester and disease the city line.

What they didn’t do, though, was go beyond the parapets, walk behind the fences that are so high they could withstand a siege, walk into the wooded areas that house thousands of Guyanese, most of whom live so far below the poverty line that they simply squat.

That part of the city was not on the roster for clean up.

It’s not on the roster for many things.

It is no secret that squatters are Georgetown’s, Guyana’s, shadow population. They live on land that is not designated housing lots so there is no city grid for them to receive postal service, they have no numbers on their houses, no basic utilities like potable water, electricity, telephone service, drainage, sewage. They live in comparative squalor in homes assembled by an artistry that would be enviable if it were not so desperate. Their homes, typically the binding together of bits of wood, brick, zinc, anything that looks element-resistant, give rise to higgledy piggledy housing settlements which accommodate the nation’s human resources and generations that are expected to be the future curators of the country.

It is hard to ignore the role of politics in the establishment and expansion of Guyana’s squatter settlements. It was easy for the PPP Administration not to make squatters more of a priority because they were shadowed by a Parliamentary Opposition that failed to keep the focus on this humanitarian crisis. Only when it was convenient, did the country’s slum cities become concern for discussion on the platforms of the PPP, a concern to which they actually offered solutions.

This Coalition government came in under a banner of a good life for all Guyanese. This would include those who live on the fringes of society, outside the fortresses erected by the opulent to keep out those who are so poor that they live anywhere.

We are not sure what specific appeal was made to them during the last election. We are not sure that they were part of the political process since their addresses are not on any official list of housing lots. We are not sure that they were even included in the country’s census taking.

We checked and discovered that Squatted was a category in the 1991 and 2002 census Ownership Status of Dwellings on page 18/25 of the PDF document of the 2002 Population and Housing Census. We saw no such delineation on the 2012 Census – no mention of category Squatter or any resemblance to any reference that would refer to that group specifically. So we don’t know if they were included in the country’s 2012 census, though the Bureau of Statistics web site, under Census, does state that there is a similarity between the 2002 and 2012 Census, that they were conducted as part of the United Nations 2010 Global Round of Population and Housing Censuses. If squatters were included, we confess that we were unable to extract that meaning and that data.

But we came away with some other information. We learnt that the 2002 Census was conducted as part of the government’s Poverty Reduction Strategy for which the Government received a loan from the Inter American Development Bank. For the loan to be granted the census had to be taken and it is our deduction that a larger number of persons counted would have justified the size of the loan either requested or suggested. The conclusion is the inclusion of squatters in the 2002 Census taking had a money incentive for a government that has a very speckled reputation on handling public funds.

The living conditions in squatter settlements are precarious, and service provision can be prohibitively expensive. Retrofitting these haphazardly constructed areas with roads and sewers and utility services may be slow, difficult, pricey, may sometimes be counterproductive but is doable with government commitment.

A few days ago Guyana’s Ministry of Communities announced that it was considering building condominiums, apartments and houses for the squatters of the Sophia Settlement in Georgetown. We weren’t surprised because it is a stated objective on the home page of the Central Planning and Housing Authority’s website. It’s objective number two.

What we didn’t hear, though, was the mechanics on how the government plans on doing this. We wondered if the construction will be done where the squatters currently live or if other lands have been ear -marked for the project. We wondered at the time frame in which the ministry proposes to resettle the squatters, given that they are just shy of the half way mark of their sunset agreement or if this is just another proposal thrown out there for appearance sake.

The Ministry has already taken the position that it will not be forced into “regularizing” by squatters who feel staying where they are will give them the land by forfeit.

We support that view to the extent that the ministry will ensure that the regularization process benefits those who are indeed destitute and are not land grabbers. In addition, with the combination of astronomical expense to retrofit squatting settlements and build new homes for squatters, we expect that the solution will be one that will make socio economic sense and not just bear out hard line sentiments.

Expropriation of land from owners may be a viable option, particularly if the government does this after indexing a buyout price to the cost owners would incur to evict the squatters and the market cost of land minus delinquent taxes…just a sample formula.

Whatever the method used, there are other social issues that have to be addressed in tandem with the proposed relocation. Decades of living in precarious social conditions cannot be undone by replacement housing. Politicians will have to eradicate the stigma associated with coming from a squatter settlement by ensuring that the communities they build are not referred to as low income or any other reference that stigmatizes occupants.

And before this happens, there has to be more real policing against squatting. The plight of squatters should never be ignored but it should not be acknowledged by allowing displaced people to just break the law.

This administration has an opportunity to show that their mission is truly a good life for all Guyanese. Inherent in this good life is the recognizing of the mandates of the country’s constitution, the country’s laws, laws at municipal level.

The idea of formalizing these housing settlements should be well formulated and well overseen. This should not be another opportunity for nefarious contracts and sole –sourcing to vendors.

If Guyana wants to claim progress, if this administration wants to have a legacy of success, it has to arrest this era of lawlessness triggered by dire and desperate need of those who have nowhere to live.

Lands that have been titled to owners, be it individuals or corporations, are lands that have ownership and should be protected against squatting in accordance with the law.

The application of the law must be impartial and cannot be forked because of circumstances. Every Guyanese, squatter or land owner, must be provided equal protection under the law.

The Ministry of Communities continues to make the provision of housing for squatters a priority. That is a good thing, considering the growing claims of displacement and homelessness. But the process has to be efficiently monitored and squatters must be given realistic time frames for relocation.

Failing this, the government, like its predecessor, will be forced to sit back and watch as squatters continue to break the law, board by board.

http://www.statisticsguyana.gov.gy/census.html

file:///C:/Users/Dell%20Owner/Downloads/Chapter7_Housing_LivingArrangements.pdf